PalmSearch Part 1: How Many Palm Trees Are there in Thousand Palms, CA?

TL; DR

This is a multi-part series on using single-shot ML algorithm to answer a very simple question: how palm trees are there in Thousand Palms, CA?

- Part 1: How hard could it be to grab some satellite data from Google Maps?

- Part 2: Big data meets bad data - generating a training dataset

- Part 3: Running YOLOv11 - How many palms are there in Thousand Palms? Did we even need to count?

If you want to run this project locally, you can find the project details on my Github. You will need an NVIDIA GPU with at least 3.5 GB of VRAM. If you can run this with ROCm, please let me know!

Introduction:

Here in California, there are plenty of towns and cities that are named after some number of trees: Thousand Palms, 100 Palms, Lone Pine, Two Bunch Palms, Thousand Oaks, Four Palms Springs, Five Palm Springs, Dos Palmas (Two Palms), Seventeen Palms, 49 Palms. Nowadays, with how easy it is to setup object detection pipelines, it should be trivial to grab some satellite imagery or Google Maps Street View data and count how many palms/pines/oaks there are in a given area. Palm trees in particular should be interested target because of their distinctive shape and height causing a large shadow to be cast when the sun is low in the sky.

I figured that this should be a simple project. Maybe an afternoon to grab the data, annotate it and train up the latest YOLO model…

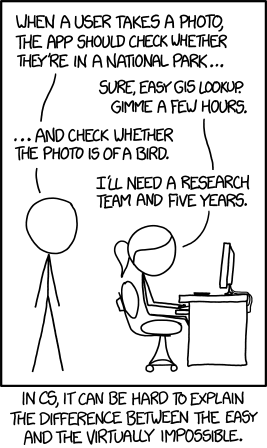

And that is where I made my first underestimation of this project. It reminds me of XKCD 1425,

As they say, “I did something not because it was easy, but because I thought it was easy”. Let’s dive in.

Working with Satellite Imagery

The first problem was determining whether satellite data would be sufficient, or whether Street View data would have to be used. The problem we need to addresss is how to convert a pair of coordinates (latitude and longitude) into a bunch of images to feed into our ML algorithm. When I started, I wasn’t sure if we could even use satellite data due to the limited resolution. The best satellite providers can do is typically 30 or 50 cm resolution. The term resolution here is technically the “ground sample distance” (GSD), or the projected distance per pixel at the surface. This number can include “super-resolution” pre-processing already applied to sharpen the image. Such high resolutions can be generated with specialized optics, such as the high resolution imager on Pleiades 1B which rocks a f/20 12.9 m focal length mirror imaging system (which beats lenses due to the need to handle VIS-NIR imaging across a wide wavelength range and SWAP packaging concerns when integrating into a satellite). 5x 6k pixel 13 $\mu m$ pitch detectors are used to give 30k pixels in the cross track for VIS-NIR imaging. Working backwards from the resolution and the focal length of the optics, we can do a bit of trigonometry to ballpark the orbital altitude of the satellites,

$$ GSD = (\mathrm{Orbital Height}) \times \mathrm{Pixel Size} / \mathrm{Focal Length} $$

which gives us an altitude of 496 km. This is a bit less than what Wikipedia reports (695 km), which tells us that the native GSD is actually 70 cm, which is then sharpened to give an “effective” number of 30 cm. Regardless, GSD/resolution is not the only paramter that matters, as we also care about our ability to resolve distinct objects. This falls under the “ground resolved distance” (GRD), which relates to the diffraction-limited resolution of the optical system. This is the best case scenario smallest distance to resolve two objects via the Rayleight criteria (basically where you could identify two separate Gaussian peaks instead of one). The GRD is given by:

$$ GRD = Orbital Height \times \frac{1.22 \lambda}{D_{Ap}} $$

which is only dependent on the aperture diameter $D_{Ap}$ and the wavelength $\lambda$. This is why the diffraction limit for IR imagery or hyperspectral imagery is typically an order of magnitude worse than the visible spectrum.

There are other factors including the modulation transfer function (MTF) and swath width that satellite imagery providers need to balance to meet their intended customer bsae (civilian, military or dual-use).

The other trick about satellite imagery is that we are not using geo-synchronous satellites that are always overhead. Most LEO satellite imagery constellations do not pass over a given area at the same time of day with each orbit. This is hepful because it means that away from solar noon, we can use the shadows cast by tall palm trees to enhance our ability to find them. Now, the professional way to do this would be to get multiple images from different satellite passes at different times of day in order to determine the ideal range of local times and the relative angle of the satellite to the surface normal (known as the nadir) to maximize the chance of palm tree detection. Unfortunately, satellite imagery from major providers (Maxar, Planet, etc.) is one of those things where prices aren’t publically listed, so if you have to ask, you probably can’t afford it. Looking around, it’s not insane at \$5-100/km$^2$, but that’s way too much for a hobby project.

I made my decision to satellite imagery the simplest way I knew - I went to Google Maps, flipped on the satellite imagery layer and zoomed into to see if I could find any palm trees. Once I found a few, I was satisfied that I would at least be able to get an order of magnitude type estimate. Next step, go harass the API!

What About Street View Data?

Now, I know that some people would have suggested starting with Street View data from Google. Even though it would have been easier to perform object detection with the large panorama images, I ruled out Street View due to the difficulty of generating a sufficient grid of images. Starting with the coordinates for a location, it would be difficult to determine exactly how to grab “all” of the different possible panoramas without tallying up a ton of API hits for possibly useless images. Additionally, there would be sizeable overlap between adjcent images and assigning uniqueness to the palm trees identified would be harder with the wide angle lenses used in Street View cameras. Also, the Street View API cost more, so I didn’t want to run out of my free credits.

Finally, Street View would only capture palms near the streets. If there were some palms hidden in someones walled compound or obscured by buildings, it would not be possible to detect them. This would preclude any palm tree farms or large properties where coverage would be poor. I saved the possibililty in the back of my head in case the satellite imagery turned out to be a dud, and trudged on with my original plan.

Generating the Grid of Images:

I decided to use the Maps Static API due to its complexity; only a single URL is needed with a pair of coordinates and zoom level to grab an image. I had also considered using the Map Tile API, but I found that the zoom level was worse than the Maps Static API. The Tile API was nice in that the data was already sorted into tiles, so generating a grid to cover a town/city would be fairly trivial. However, I found out that the Tile API did not have the same zoom levels as the Maps Static API, so I had to ditch it.

THe only trick with the Maps Static API was that since each image was generating by the coordinates (latitude and longitude), the zoom level (0-22) and the size (using 640x640 pixels), there was some math involved to figure out what to shift the coordinates to avoid overlap between tiles while also not missing anything in between. Google uses the Mercator projection to map coordinates to pixels - what this means is that at different latitudes, the pixel to ground distance will change. If you are not yet a map nerd, you can go become one as you read through Mercator projection calculations. Safe to say, we just have to use math to figure out what the latitude and longitude we need to use to get a perfect grid with a spacing of 640 pixels between center locations.

Finally, generating the grid can be done one of two ways: generate only the grid as specified by some bounding boxes (which we can get Google to provide for us via their geocoding API which is used to generate town/city/county/state limits), or by generating a larger grid and then filtering out points outside our region of interest. Some basic approximation for the space/cost for this grid is: the API cost is around \$2/1000, ech tile is something on the order of 50 m and Thousand Palms is around 2 miles square, so the grid of 64x64 tiles or ~4000 tiles gives us a total cost of $8. Each image is 640x640 pixels as a png8 and is around 200 kB in size, so our grid is around 800 MB. Totally doable.

Summary:

What did we learn? We figured out that we can use the Google Maps API to generate satellite imagery at sufficiently high resolution to make out some palm trees by eye - bonus points for regions where imagery was captured when the sun was low in the sky, giving nice shadows that we can use in the next part for annotating our images. All of this without having to break the bank getting some very nice satellite imagery from a data broker. There was also some trigonometry needed to setup a grid of adjacent non-overlapping images encoded by latitude and longitude starting from some center point and using the image size of 640x640 pixels. Armed with our grid, we can move on to the next step: generating annotations for our training dataset and playing around with YOLOv11 to run the object detection.