Star Tracking in the Era of GPS

Origins and Uses of Star Tracking

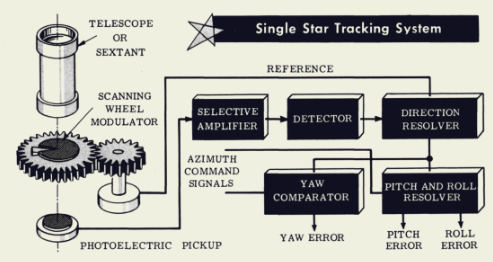

Before the development and deployment of GPS satellites and high precision inertial measurment systems (IMS), in the 50s and 60s the highest precision guidance systems were based on star trackers. These were used on long-range missiles to compare the stars in the field of view to a reference database. By itself, a single star tracker could be sufficient as a reference to give feedback on the pitch, roll and yaw error, but would require the tracker to be centered on the star with its own degrees of freedom relative to the host object. Combining a star tracker as an attitude reference with an accelerometer and gyroscope would provide real-time feedback and correction for any drift in the accelerometer and gyroscope 1. While star trackers remain a relatively niche in the era of GPS, they remain relevant for satellites that may operate in orbits outside of LEO where GPS is less reliable, or in current conflict zones where GPS signals are easily jammed.

Star tracking still plays a major role in satellite systems as seen by the significant CubeSat commercial market. If you have upwards of $10,000 - $100,000, you can get a lightweight integrated lens and camera system qualified for space to get incredibly tight tolerances on attitude feedback for an IMS (down to arcseconds/milli-degrees), as well as the functionality to perform a lost-in-space protocol to initialize the IMS and to provide feedback to correct the inherent drift in an IMS.

For ground based systems, GPS (or equivalent navigation satellite system system, such as GLONASS, IRNSS or BDS), the ease of use and precision makes GPS integration easy and cheap. GPS accuracy can be enhanced from the lower limit of $\sim$0.1 m with a real kinematic (RTK) receiver base, which provide a reference for mobile units to determine their distance more precisely 2. For applications such as surveying or drone-based imaging, the spatial resolution can be improved down to $\sim$ 10-30 mm. Even if you are planning on operating in a “GPS-denied” region, the inherent disadvantage of star trackers compared to other attitude systems such as radio or magnetic sensors is… the need to see stars. For all practical purposes, a terrestrial star-tracker in the visible range can will only work during night time hours. There are exceptions to this rule 3, but the vast majority of projects would be better off with a GPS sensor unless extremely high angular precision is required.

The Lost-in-Space Problem

The main goal of a star tracker in space is to be able to provide orientation feedback to the IMS. If we want our satellite to maintain a given orientation $(\theta,\phi)$, but the IMS gyroscopes exhibit some drift rate (say 0.1 deg/hr), then after a day or two of staring at the same patch of space we could be off by a few degrees! We need a set of reference points to use to correct the drift that occurs in the instruments. The “lost in space” (LIS) problem, as the name suggests, deals with essentially being able to “home” the IMS to provide an initial reference point. There are two general ways to do this, each with their own tradeoffs. The main technique is take an image (or several) and perform pattern matching on the stars observed to a reduced dataset of known patterns from a database made from a star survey.

The main driving constraints are the field of view (FoV) of the star tracker system and the minimum resolvable stellar magnitude (a larger number is less apparent brightness). Then the problem becomes the issue of matching the observed pattern of stars to a pre-computed database. Historically, due to the memory constraints on satellite systems, it was not feasible to just chuck the whole star catalog and call it a day. The main difficult lay in how to encode the pattern matching in a memory efficient way that can stil be done quickly and on the fly on-satellite.

With a known FoV and limit on magnitude, the number of stars per FoV can be calculated. For a given FoV, the star pattern can be encoded and stored in a hash table based on simple two star pair-matching based on angular distance or a more complicated 3+ star geometric algorithm. There is always the probability that in some number of FoVs, there will not be a unique match to our hash table - in that case it is part of the system design that needs to consider alternatives and determine how far the satellite should rotate along the various degrees of freedom to try again.

For those interested in more details, please see this nice 2020 open-access review on LIS algorithms or slightly older 2009 article on the details of the algorithms.

Conclusions

Even though GPS positioning can still be used for satellites in low Earth orbit (LEO) and is a much nicer turn-key solution for positioning when accessible, I find star trackers interesting because they combine optics and imaging systems with the complexity of how to encode the amorphous idea of “star patterns” into a concrete value that can be used for quick lookup with a hash table or data base.

-

See the “Basics of Missile Guidance and Space Techniques” by Marvin Hobbs (1959) for more details on various 50s and 60s control schemas coming out of WW2 era fire control. ↩

-

For those interested in RTK, I’d recommend the Sparkfun website for the kinds of projections and applications where GPS-RTK systems provide a significant precision advantage over standard GPS sensor (along with a price increase). ↩

-

See news release by Goddard on high altitude balloon daytime trackers. Notice how much larger the star tracker unit is compared to the Cubesat designs! ↩